I read a lot. I like learning and I like problems. But my biggest problem, and the lesson I’ve constently failed to learn, is that I forget almost everything. I’ve read whole shelves of books I couldn’t tell you a single thing about.

I don’t have the best memory in the world, but as memories go I think mine is pretty good. Yet I have this problem just like many other people. Simple aptitude for recall isn’t the problem. The problem is forgetting to think about your future self. It’s not being mindful of the fact that you are, despite your lofty estimations of yourself, an ape. You might be holding a macchiato, but you’re still an ape.

From an evolutionary perspective, there is actually benefit to forgetting most of everything you experience. Only a handful of things are worth keeping, namely those that might increase your chances of staying alive. As Matthew Walker explains in Why We Sleep, this process of pruning out the unimportant stuff is one of the crucial operations carried out when you sleep.

Using How Memory Works to Your Advantage

Despite every pop-sci documentary I’ve ever seen, human memory does not function like a computer hard drive. On a hard drive you can dump anything you like, in any format you like, with as much or little organisation as you choose, and the drive will faithfully store it all with equal fidelity.

Our brains aren’t like that at all. If you put crap in, you don’t even get crap out. You get nothing out at all. Because the human brain is an expert at filtering out crap – except advertising jingles, of course.

As James Clear explains in Atomic Habits, retaining semantic knowledge (facts and arguments and philosophies) requires structure. That means at least some form of processing of that information, and recitation. Turning it into a story that means something to you is a powerful tool used by champions of memory contests (they had a good section on it on the Memory episode of Netflix’s The Mind Explained).

You need more than the willpower to remember something. You also need to avoid overestimating your faculties. Countless times I’ve failed to consolidate my understanding of a concept, because it seemed so ridiculous that I would just forget something so important and useful. I would then promptly forget it, left with only the vague impression of having had known it.

My Note-Taking System

So I’ve decided to start fixing that. Finally.

I’ve adopted a method that incorporates two aids to good retention: recitation and storymaking. Inspired by David Sedaris, Austin Kleon and Jake Knapp & John Zeratsky’s Make Time, I’ve committed to a combination of stream-of-consciousness and reflective journaling:

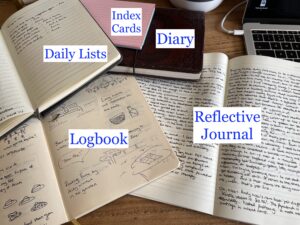

- A book of lists. I make a new list each day, in the style of Make Time: split into my daily highlight, my must-do tasks, and my might-do tasks.

- Keeping a reflective logbook of noteworthy things from the previous day. They don’t have to be “important”, just noteworthy to me. Graduating my PhD program and having some great pancakes are both on the list.

- Each morning I make an entry in a journal. This is the big one for me. I’ll do a full post on this separately, but it’s another thing I pinched from various other people (I came across it via Austin Kleon, but the concept is covered extensively by Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way: Morning Pages. It’s just a page a day.

- I still keep a standard diary for stream of consciousness outlet, which I leave to whenever I feel the need.

Progress So Far

I’ve built this system over the last few months. I take no credit for it, it’s a mongrel of other people’s excellent ideas. It’s just my take on it. I do it all longhand, in different books that I keep close to hand. I also keep index cards on my desk to jot down fragments as they occur to me, to be written up in full the next day.

From all this, I can collate some ideas of what I want to work on creatively, and what I write on here. It’s not a comprehensive personal Wiki, but a system of highlights and triggers, to activate the right neural pathways that reinforce a memory. This means I can summon what I’ve been thinking about and learning recently and combine it in new ways.

I’ll also be using the system to generate my recommendations that will feature in my newsletter, once I get it off the ground.

The Power of Revision

The aspect that is easiest to overlook is the importance of revisiting what you’ve written. No tool will give you the ability to write something down once and then file it away forever, and still give you the benefit of better recall. The whole point is to generate a resource that you can continually immerse yourself in, like Sherlock Holmes’ Mind Palace, only… well, really it’s just a big pile of actual filing cabinets full of paper.

The point is that you’re extending your mind beyond the scope of the neurons inside your skull. I would argue that it’s not a second brain. This kind of note-taking system isn’t a knowledge bank itself, but rather a way of capturing proccessing-in-progress, in paper (or digital) form, rather than relying on your crap short-term memory.

I’m not sure if it’s something I’ll maintain, or how effective it is. But it’s at least a bit effective – this post wouldn’t be here otherwise.