The most regretful people on earth are those who felt the call to creative work, who felt their own creative power restive and uprising, and gave to it neither power nor time.

– Mary Oliver

If you let it, the chaff of life will crowd out your true purpose. Without conscious curation, life falls onto default rails, and and it is possible to spend years on what is fundamentally unfulfilling.

Over 10 years ago, when I was 19, I finished my fourth novel. I was surprised to find it wasn’t obviously a steaming turd, so I decided to try and get a literary agent. (An adorable story, involving me writing my age on the cover letter, as though to assure them I wasn’t actually three toddlers in a trench coat.)

Some of my friends laughed at me, for writing nerdy fiction for nerds, and for aspiring to anything loftier than a birthday party at All Bar One.

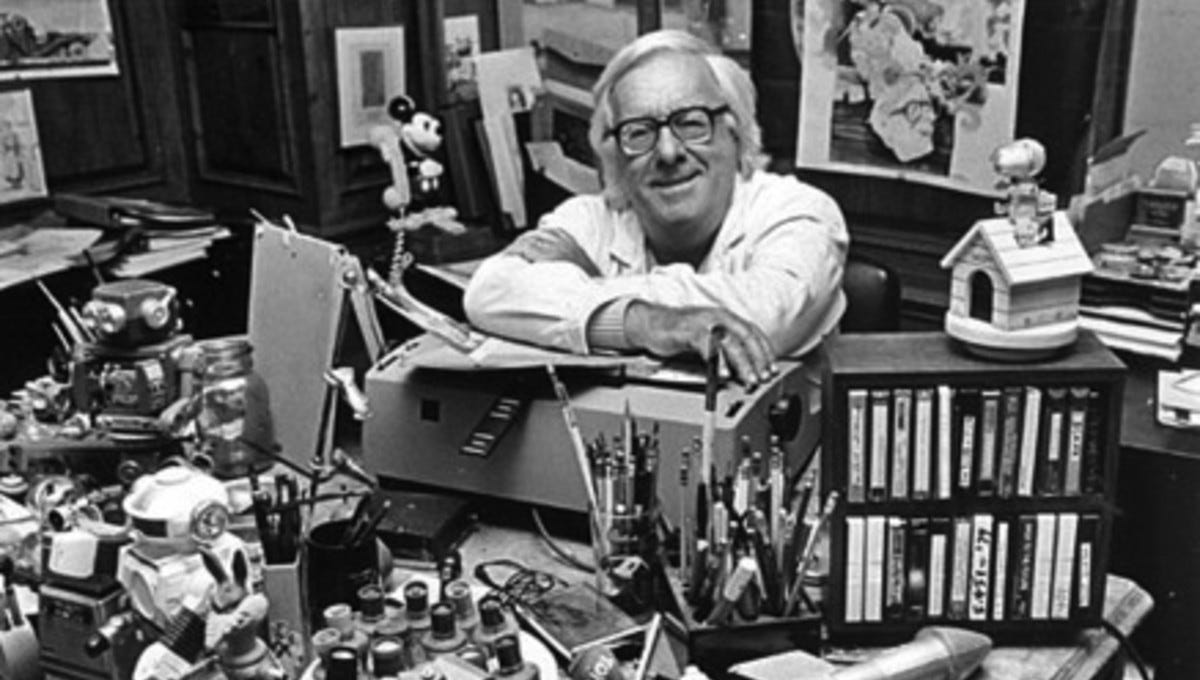

I wasn’t quite old enough to realise that friends who laugh at you for trying to grow are not friends at all. Nonetheless, I didn’t have time for their crap. As Ray Bradbury famously said:

“I have never listened to anyone who criticized my taste in space travel, sideshows or gorillas. When this occurs, I pack up my dinosaurs and leave the room.”

I read every guide on the publishing business I could find, and started querying.

A year later, I signed with an agent, delirious with excitement.

It didn’t go well. By the time I was 21, we parted ways and I set out to publish the books independently admist the self-publishing revolution. It was 2013, the crest of the ebook gold rush.

I released five books over three years, and featured in a series of short story anthologies. My degree and subsequent PhD gradually took over, and the writing got pushed onto the back burner. I was satisfied with what I’d accomplished, so I let it slide further and further back, until it became not something I do but something I used to do.

More recently, with my doctoral studies coming to an end, it looked like I would finally have the time and energy to return to writing in a serious way. I couldn’t help wondering why I had stopped in the first place. I’d had a great time, after all.

Except, I have a journal that says otherwise. It tells a totally different story. As a friend of Greg McKeown once said to him:

“The faintest pencil is greater than the strongest memory.”

Looking through that journal, the signs of burnout are obvious. There had been ups and downs, but it’s clear that, at some point, it had simply stopped being fun. I suspect that juggling it all meant that I ended up treating it like a chore, rather than something I enjoyed. And something with a long payoff horizon is unsustainable if you get no enjoyment from it.

The key to avoiding burnout in doing what fulfils you is to have some fun with it.

The key is play.

The ideal work is that which feels like play. We’re socialised to think the opposite from a young age. Ken Robinson has a spectacular TED talk about the school system killing creativity (see below). I remember first watching the talk in 2015 and emphatically agreeing: play and exploring are vital to self-actualisation (see Maslow’s Pyramid).

Then I proceeded to grind away in a playless desert for years.

Being aware of a fault doesn’t automatically change your behaviour. Habits are difficult to form deliberately. As explained in this Freedom article, “According to a 2010 study published in the European Journal of Social Psychology, it took study participants anywhere from 18 to 254 days to carry out an eating, drinking or activity behavior habitually, with an average time period of 66 days.”

Maintaining the space and time for play requires commitment.

Sounds odd. Committing to play.

But in the modern world, that’s exactly what it takes. Greg McKeown talks about this very thing in Chapter 13 of Essentialism: subtraction. Cut away all the non-essential chaff of life, leaving the single thing you want to use your energy on (more about that here).

McKeown quotes what is apocryphally attributed to Michaelangelo, which I’ll paraphrase here:

When asked how he accomplished the feat of carving his masterpiece, the statue of David, Michaelangelo replied: “It’s easy. You just chip away everything that doesn’t look like David.”