I had hoped to write some kind of end of year post in December 2024. Maybe even a brief newsletter. But neither of those things happened. I don’t know how people get around to it. Oh well, better late than never.

Continuing on from reports in 2022 and 2023 (inspired by a similar analysis from Kate McKean’s excellent newsletter), here’s the breakdown for the books I read in 2024. The list includes things I finished, but also DNFs if I finished an appreciable portion of the book before putting it down.

I read 66 books in 2024. I can immediately report that I read a lot of short fiction on my e-reader, and listened to a lot of podcasts. But beyond that, I need to dig into the numbers.

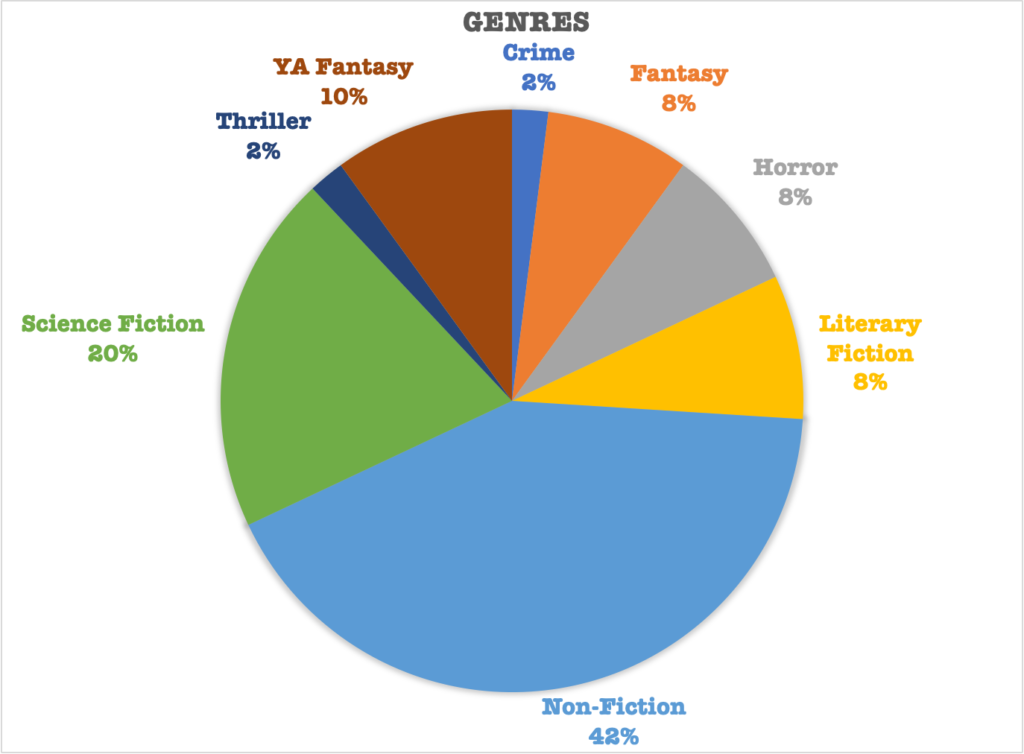

Genres

Slightly more fiction this year, but it seems like I naturally gravitate to a 50/50 split on fiction/non-fiction. More sci-fi than last year, but much less fantasy. Surprising—I hadn’t noticed the lack of fantasy.

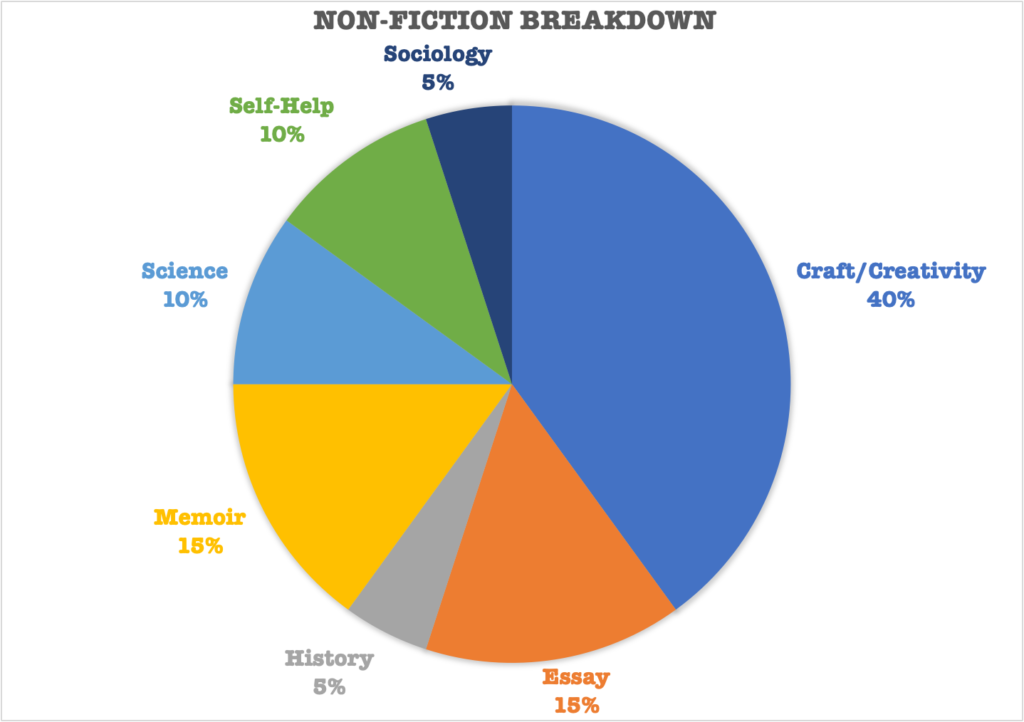

A closer look at non-fiction

Overall this more closely resembles 2022 than 2023. Apparently I got a taste for books on writing craft this year—interesting, given I wouldn’t have guessed that. Memoir was still big but tied with science—again, surprising, as I would have said I read much more science. I picked up a lot of other interesting things this year in non-fiction, and it’s nice to see that reflected here.

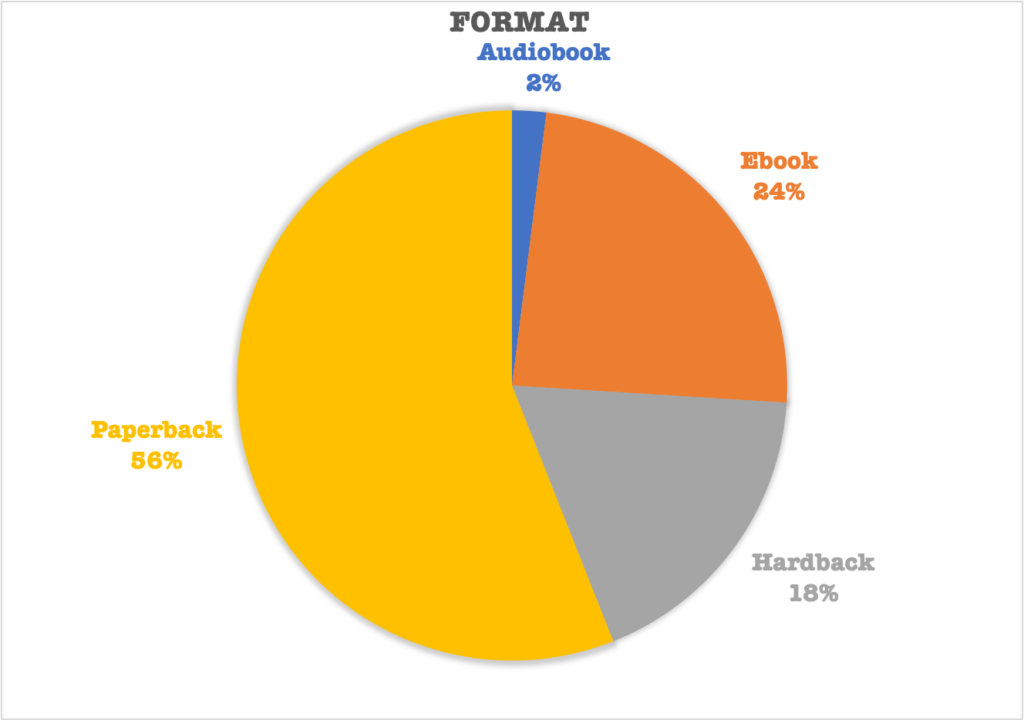

Book formats

As usual, mostly paperback. My audiobook listening was almost nonexistent. I was aware that I picked up a lot of hardbacks this year, which was a real joy. However, I hadn’t really appreciated just how few ebooks I read this year. I have been reading a lot of short fiction on my e-reader, which probably accounts for my lack of awareness.

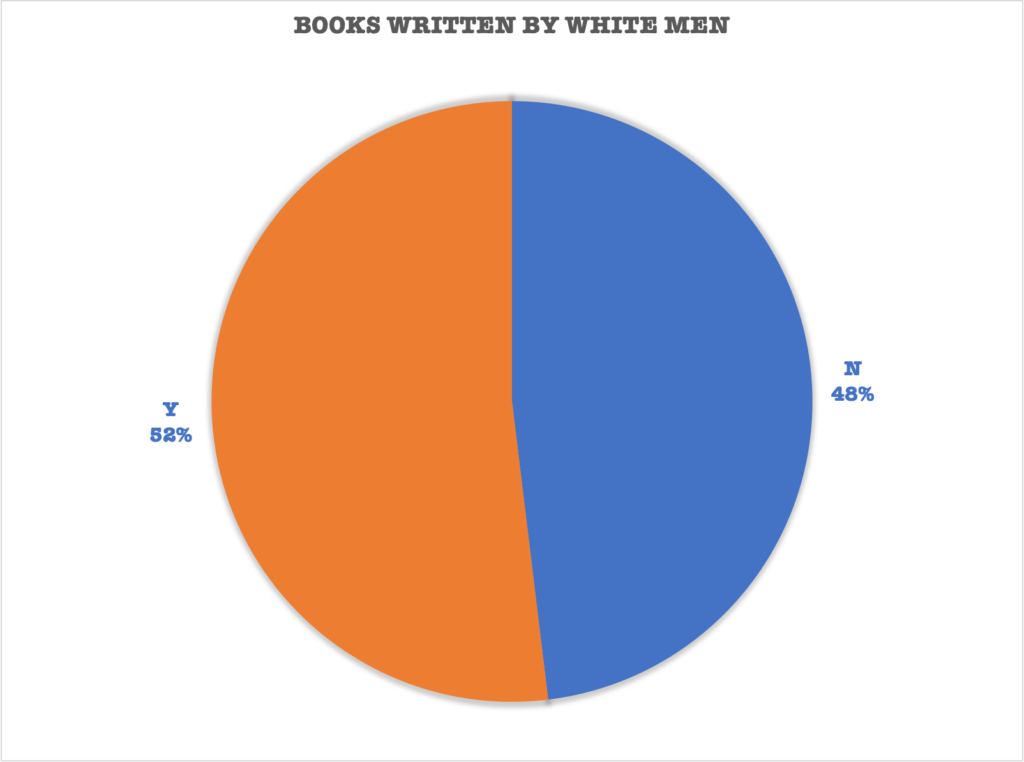

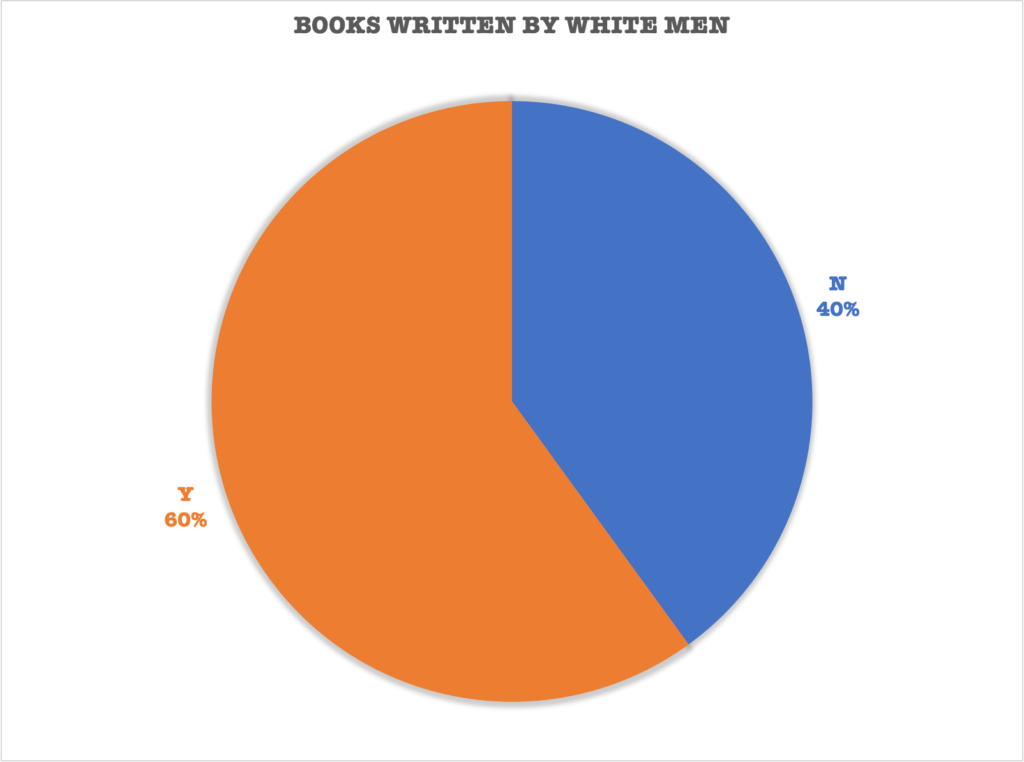

Minority voices

Still on an upward trend here (60/40 in 2022, 52/48 in 2023). I recall putting in a lot of effort on this in 2022, and somewhat in 2023, but I hadn’t really paid any attention to this in 2024 beyond noticing that my bookshelf looks more diverse than it used to. It’s nice to see that this has become more of a sustained habit that I don’t have to consciously maintain.

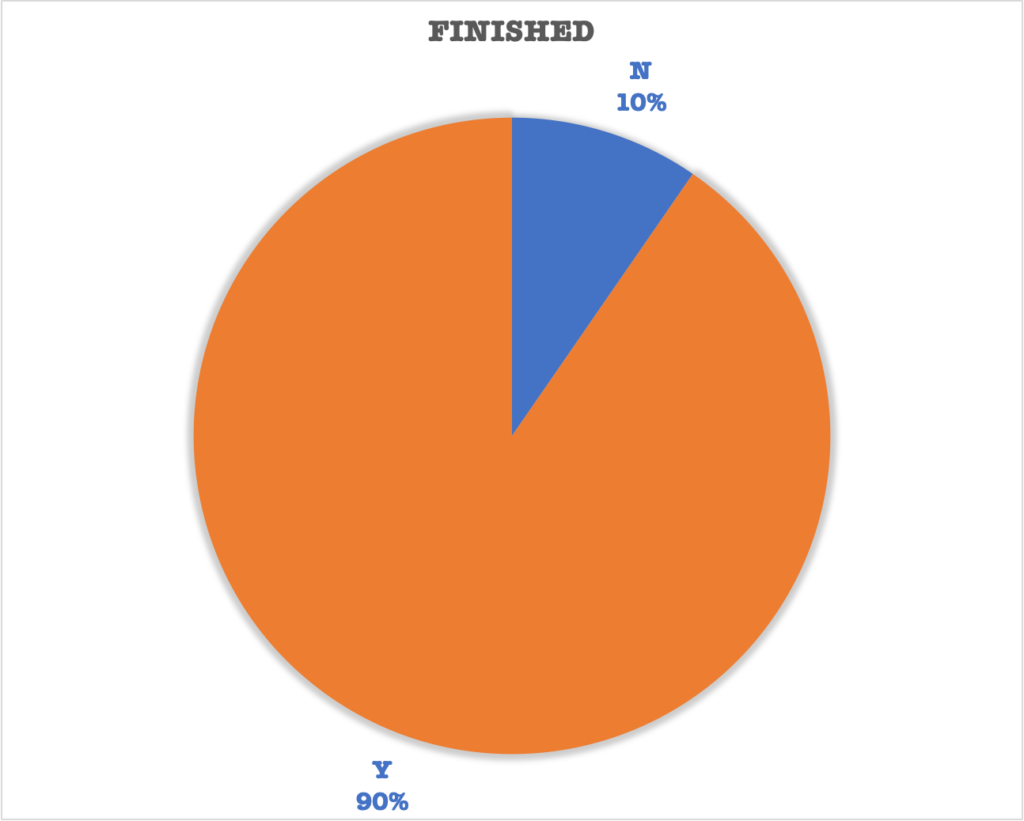

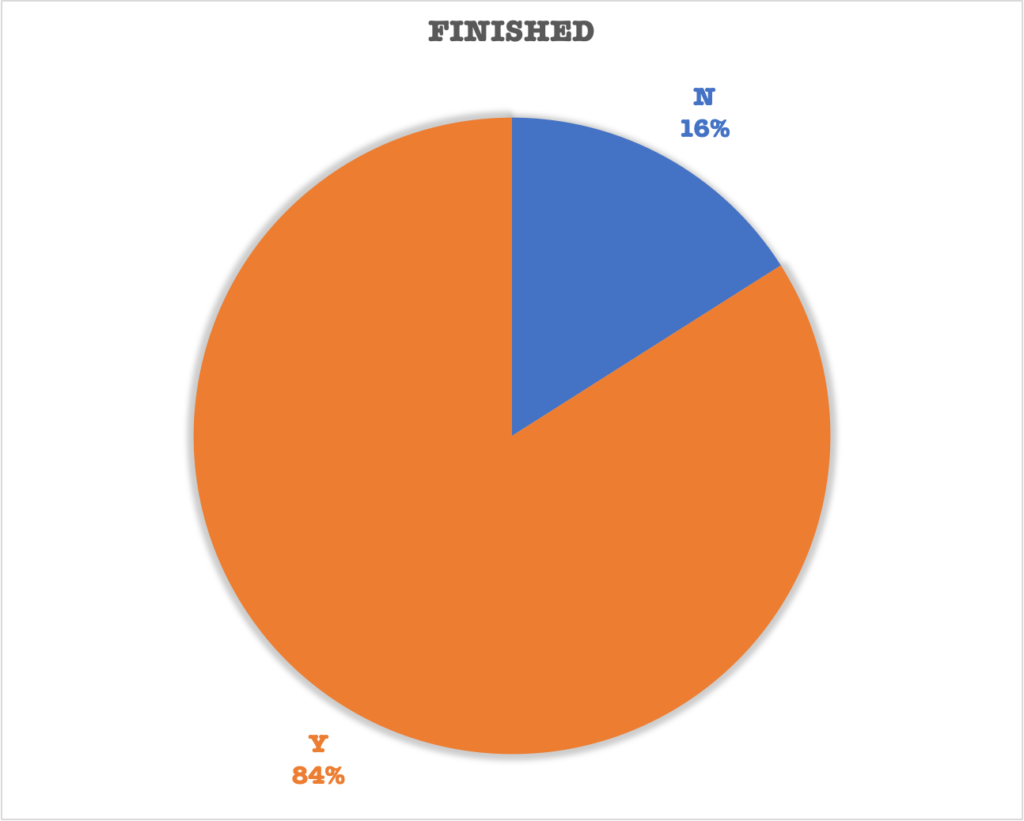

Completed vs partial reads

I count books as ‘read’ on my log even if I don’t read them cover to cover. As a rule of thumb, if I get more than halfway, I’ll count it. I DNFed 8 books this year, roughly the same percentage as last year. Looking at the books in question, they were mostly longer works that, for me, seemed to fizzle out.

For reference, here’s the list (see the Book Log for previous years):

- Wonderbook by Jeff VanderMeer

- The Fran Leibowitz Reader by Fran Leibowitz

- Drown by Junot Dîaz

- Payback by Margaret Atwood

- Singin’ and Swingin’ and Gettin’ Merry like Christmas by Maya Angelou

- Steering the Craft by Ursula K. Le Guin

- Breakfast at Tiffany’s by Truman Capote

- On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong

- The Mountain in the Sea by Ray Nayler

- Meander, Spiral, Explode by Jane Alison

- Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino

- South of the Border, West of the Sun by Haruki Murakami

- Religion for Atheists by Alain de Botton

- Two Cures for Love by Wendy Cope

- The Parable of the Sower by Octavia E. Butler

- And Still I Rise by Maya Angelou

- The Peace of Wild Things by Wendell Berry

- An Unquiet Mind by Kay Redfield Jamison

- Where Good Ideas Come From by Steven Johnson

- Hyperion by Dan Simmons

- The Fire of Joy by Clive James

- Autobiography of a Face by Lucy Grealy

- Milk and Honey by Rupi Kaur

- Skyward by Brandon Sanderson

- When You Are Engulfed In Flames by David Sedaris

- Ariel by Sylvia Plath

- Inferno: A Memoir of Motherhood and Madness by Catherine Cho

- All the Names They Used for God by Anjali Sachdeva

- The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee

- Poems of Thomas Hardy by Thomas Hardy

- Upstream by Mary Oliver

- Essays in Love by Alain de Botton

- The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

- Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu

- Mexican Gothic by Silvia Moreno-Garcia

- Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke

- Legends and Lattes by Travis Baldree

- The Dark Forest by Cixin Liu

- Oathbringer, Part 1 by Brandon Sanderson

- The Haunting of Hill House by Shirley Jackson

- The Time Hunter by Italo Calvino

- The Driver’s Seat by Muriel Spark

- Selected Poems by E. E. Cummings

- Serious Concerns by Wendy Cope

- The Salt Path by Raynor Winn

- One Day by David Nicholls

- Howard’s End is on the Landing by Susan Hill

- Hallucinations by Oliver Sacks

- Selected Poems by W. H. Auden

- How to Avoid a Climate Disaster by Bill Gates

- A Memory Called Empire by Arkady Martine

- Quiet by Susan Cain

- Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

- Collected Poems by Simon Armitage

- How to Be A Woman by Caitlin Moran

- Ascension by Nicholas Binge

- How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan

- The Writing Life by Annie Dillard

- Think by Simon Blackburn

- Wool by Hugh Howey

- Grit by Angela Duckworth

- A Poetry Handbook by Mary Oliver

- Sentience by Thomas Humphrey

- There Is No Antimemetics Division by Qntm

- The Sun and Her Flowers by Rupi Kaur

- Novelist as a Vocation by Haruki Murakami